Reprogenetic News Roundup #9

Embryo selection, East-Asian competitiveness, BridgePRS, the Tárnoki twins, genetics of faces...

Welcome to this Christmas edition of the Reprogenenetic News Roundup! Here’s this issue’s content at a glance:

Repro/genetics: practices, policies & debates

Julian Savulescu and colleagues discuss optimal novel embryo selection strategies that increase benefits and reduce risks for parents and children.

Dr. Alexis Heng argues that in hyper-competitive Asian societies like Singapore “permitting IVF polygenic testing is a slippery slope to genome editing.”

Rei Tachibana and Toshiyasu Ando’s Luck Is Hereditary: The Laws of Success Taught by Behavioral Genetics is proving a best-seller in Japan with 30,000 copies printed so far.

Genetic Studies

BridgePRS, a novel Bayesian polygenic risk score (PRS) method, promises to increase the predictive power of PRS beyond Europeans to other genetic populations.

The Times Higher Education interviews Ádám and Dávid Tárnoki, radiologists and twin researchers who are themselves identical twins, covering the value of twin studies and their own intertwined lives.

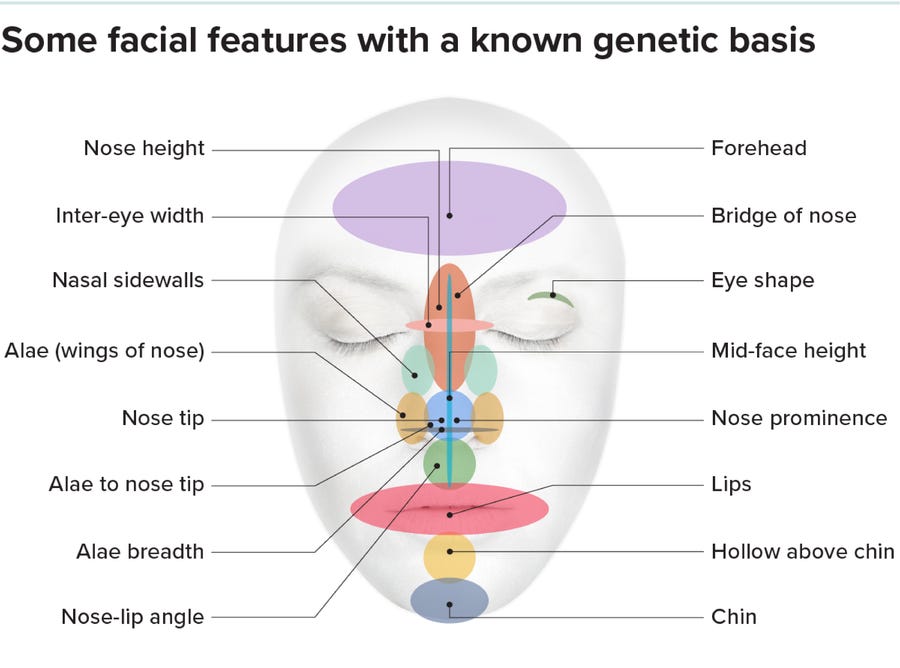

Scientific American interviews researchers exploring the complex genetics of faces.

Using aggregate human genome data for individual identification

Individual studies: physical activity and mental health, major depression (multi-ancestry), anxiety (Kyoto University), alcohol-related cirrhosis, alcohol alcohol metabolism and atrial fibrillation, alcohol use frequency, epilepsy,

Everyone at the Genetic Choice Project wishes you a Merry Christmas and prosperous New Year!

Repro/genetics

“Novel embryo selection strategies—finding the right balance” (Frontiers in Reproductive Health)

Alex Polyakov, Julian Savulescu, and colleagues discuss ethical considerations and risks surrounding the use of novel embryo selection technologies in IVF, including the growing uptake of genetic testing.

The authors argue prioritizing embryos for transfer into the uterus using these technologies is acceptable, as this may result in a higher chance of an earlier and successful pregnancy and a healthy child.

However, discarding embryos based on unproven advances should not be allowed, as this may lead to the discarding of actually healthy embryos and reduce the chance of prospective parents achieving pregnancy. The authors provide several examples of this occurring due to premature adoption of reprotechnologies.

The authors assert the primacy of patients’ autonomy in reproductive decision-making, especially when information gained from novel technologies is imprecise.

In IVF, more than one embryo is often available for transfer to the uterus. The traditional approach is to transfer the “best” embryo first, conventionally defined as an embryo with the highest potential to result in a viable pregnancy.

Numerous developments in reproductive medicine attempt to improve embryo selection to achieve pregnancy sooner, such as AI, embryo genetic testing for aneuploidy, and time-lapse analysis.

Embryo selection is typically based on two criteria: the shortest possible time to pregnancy and the prevention of children being born with conditions that will significantly adversely affect the length or quality of their life. The second criterion, notably when selecting against a disability, is sometimes controverisal but widely accepted among health professionals and many ethicists.

The authors propose these criteria for embryo selection:

An embryo with the highest chance of producing a pregnancy is transferred first, thus reducing the time to pregnancy.

Embryos suspected to harbor an abnormality that may produce a child with a significant disability may be transferred only rarely, under specific circumstances, where all other reproductive options have either been exhausted or are not acceptable.

The overall cumulative pregnancy rate from a batch of embryos derived from a stimulated cycle must not be reduced by discarding embryos that may have a normal reproductive potential. (So as to not reduce prospective parents’ reproductive autonomy.)

“Permitting IVF polygenic testing is a slippery slope to genome editing in hyper-competitive Asian societies like Singapore” (Bioedge)

Dr. Alexis Heng highlights the interaction between the “hyper-competitive social norms and Confucian values of various East Asian societies that emphasize hard work, frugality and education,” “tiger parenting,” and emerging reprotechnologies.

In East Asia, many parents compete to get their children into the best schools even before they are born, notably through expensive purchases of residential properties near prestigious elementary schools.

The author argues this is most apparent than in Singapore, which has a prevalent “kiasu” (afraid to lose) mentality. Parents spend a large proportion of their income on after-school tuition fees. “Tiger parenting” also extends to recreational activities such as music, sports, and art, whereby parents enter their children into competitions and inculcate the principle of trying to excel in everything they do.

Dr. Heng notes the “major confounding factor” in every parent’s plans as the randomness and unpredictability of the natural process of fertilization. As a result, there is always the worrying possibility that a child born of high-achieving parents may not necessarily be a high-achiever.

The advent of polygenic scoring in preimplantation genetic testing (PGT-P) of IVF embryos could possibly provide a solution by selecting for health or other phenotypic traits. AI algorithms are specifically being developed for such complex screening and analytical processes in polygenic testing.

In August 2022, researchers in China used polygenic testing to select IVF embryos with less risks of developing family-related diabetes.

There are minimal risks involved in polygenic testing and selection of IVF embryos, because there are no permanent man-made genetic modifications. Dr. Heng describes the technique as one of “picking the winning ticket” in the “genetic lottery” of fertilization for good health, intelligence and, other socially-desirable traits.

A large-scale survey released in Science showed that 38% of U.S. respondents would use polygenic testing to improve their child’s IQ and academic performance to better their chances of entering an elite college. Dr. Heng believes the figure would be much higher in Singapore.

Dr. Heng believes Singapore would “very likely” ban polygenic testing of IVF embryos for selection of non-disease traits such as intelligence, while allowing its use for prevention of complex multi-factorial diseases such as type 2 diabetes. This could enable a “slippery slope” where screening for genetic risk of diseases enables secret screening for “non-disease socially-desirable traits such as intelligence, tallness and fair complexion,” especially as prospective parents will have the necessary genetic data from the embryos.

Dr. Heng flags the risk of disappointment and frustration if PRS does not result in the “dream child,” leading to pressure to adopt human genome editing.

Dr. Heng concludes that IVG polygenic testing could be a like a gateway drug and slippery slope towards human genome editing “in a hyper-competitive Asian society like Singapore.”

More on repro/genetics:

“Urgent call to expedite glaucoma genetic test for sight-saving” (Mirage News, Australia)

“Thalassemia screening in Thailand: Medical Sciences Dean advocates for elevated trust” (EurkAlert!)

Japanese authors Rei Tachibana and Toshiyasu Ando’s Luck Is Hereditary: The Laws of Success Taught by Behavioral Genetics is having a fourth printing to meet demand, with 30,000 copies so far. (PR TIMES)

Genetic Studies

“BridgePRS leverages shared genetic effects across ancestries to increase polygenic risk score portability” (Nature Genetics)

BridgePRS is a novel Bayesian polygenic risk score (PRS) method that leverages shared genetic effects across ancestries to increase PRS portability.

BridgePRS’s validity was evaluated using UK Biobank and Biobank Japan data aross 19 traits in individuals of African, South Asian, and East Asian ancestry.

The authors conclude BridgePRS is a computationally efficient, user-friendly, and powerful approach for PRS analyses in non-European ancestries.

“We think the same, say identical twin researchers studying twins” (Times Higher Education)

Hungarian researchers Ádám and Dávid Tárnoki have an unusual advantage when recruiting participants for twin studies: being twins themselves.

“We had a sleep study where the twins had to sleep overnight at Semmelweis University and undergo many blood tests and sleep tests, with many cables on their bodies,” Ádám said. “It was not so convenient, so we decided to be the first twin pair and share our experiences. Almost 80 or 90 twin pairs ultimately participated.”

The Tárnoki brothers, alongside Júlia Métneki and Levente Littvay, began work to revive the defunct Hungarian Twin Registry in 2006, establishing an official population-based registry in 2021. Today, the registry has more than 10,000 enrolled twins, enabling the Tárnokis to conduct imaging-based studies. Ádám is also nearing the end of his term as president of the International Society for Twin Studies; when he steps down, Dávid will succeed him.

“Why are twin studies special? Because the twins are born at the same time, they spent time in utero in the same environment, most of them share their early life until they become adolescents, so the common environment is the same,” Ádám explained.

Studying twins enables researchers to examine the environmental and genetic influences on the development of diseases or traits. The Tárnokis have studied the heritability of atherosclerosis, a key risk factor for heart attacks and strokes, as well as the impact of the gut microbiome on the development of dementia and breast cancer.

Twin research is not the brothers’ primary occupation: both are radiologists at Semmelweis University’s medical centre, while at the National Institute of Oncology Dávid leads the imaging centre and Ádám is head of the radiology department. Both teach at Semmelweis University and supervise PhD students. “It’s an advantage to be twins because we can share the work. One part of the job is performed by Ádám, the other by me,” Dávid said.

In secondary school, the twins shared classes: “We studied together from one book, so we could discuss it and more easily prepare for exams,” Ádám said.

Both twins specialized in radiology. “We share 100% of our genes as monozygotic twins. We have the same interests,” Dávid said. But they didn’t pursue completely identical careers, Ádám said: “I study nodular and oncological lung disorders, and Dávid studies interstitial lung disease.”

The Tárnokis spend most of the week working together, but rarely tire of each other or feel a sense of competition: “We don’t fight, or it’s extremely rare, because we’ve seen that it makes no sense to do it. It’s not advantageous to us to fight,” Ádám said. “I know what he’s thinking because we usually think the same, or at least very similarly. This is why our working pair is more effective.”

The brothers spend time apart on weeks, typically devoting them to their families. Both twins are married; each brother has two young daughters. “It’s funny,” Dávid said. “We have the same trajectory.”

“The genetics of why you look like your great aunt Mildred” (Scientific American)

Scientists are discovering that hundreds if not thousands of genes affect face shape.

Benedikt Hallgrímsson, a developmental geneticist and evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Calgary (Canada), is researching how to genes may work as “teams” in facial development.

Some 25 GWASs of facial shape have been published to date, with over 300 genes identified in total. “Every single region is explained by multiple genes,” says Seth Weinberg, a craniofacial geneticist at the University of Pittsburgh. “There’s some genes pushing outward and others pushing inward. It’s the total balance that ends up becoming you, and what you look like.”

The genetic variants uncovered thus far don’t account well for the specifics of each face. In a survey of the genetics of faces in the 2022 Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, Weinberg and his colleagues gathered GWAS results on the faces of 4,680 people of European ancestry: known genetic variants explained only about 14% of facial differences.

Certain parts of the face, including the cheeks, lower jaw and mouth, seem more susceptible to environmental influences such as diet, aging and climate.

Hallgrímsson argues that if faces were simply the sum of hundreds of tiny genetic effects, as the GWAS results imply, then every child’s face should be a perfect blend, halfway between its two parents. Families show this is not the case. “My son has his grandmother’s nose,” says Hallgrímsson. “That must mean there are genetic variants that have large effects within families.”

Certain genes may have large effects on face shape within families but be rare in the general population. “Facial shape is really a combination of common and rare variation,” says Peter Claes, an imaging geneticist at KU Leuven in Belgium. As an example, he points to French actor Gérard Depardieu’s distinctive nose. “You don’t know the genetics yet, but you feel this is a rare variant.”

A few other distinctive facial features that run in families, such as dimples, cleft chins, and unibrows, could also be candidates for such rare, high-impact variants, says Stephen Richmond, an orthodontic researcher at the University of Cardiff, Wales, who studies facial genetics.

A study by Sahin Naqvi, a geneticist at Stanford University, and his colleagues has highlighted the role of genes that regulate others in facial development.

More on genetic studies:

“Effects of physical activity and sedentary time on depression, anxiety and well-being: a bidirectional Mendelian randomisation study” (BMC Medicine)

The study found sedentary time and lack of physical activity impact a range of mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, and well-being.

“Multi-ancestry GWAS of major depression aids locus discovery, fine-mapping, gene prioritisation, and causal inference” (bioRxiv)

“Primary aldosteronism and lower-extremity arterial disease: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study” (Cardiovascular Diabetology)

“Kyoto University successfully maps genes related to anxiety disorders and the brain regions in which they are expressed” (Tech Plus)

“Study shows synergistic effects of genetic factors, binge drinking, and diabetes in alcohol-related cirrhosis” (News Medical)

“Risk of newly developed atrial fibrillation by alcohol consumption differs according to genetic predisposition to alcohol metabolism: a large-scale cohort study with UK Biobank” (BMC Medicine)

“A developmentally-informed genome-wide association study of alcohol use frequency” (Behavior Genetics)

“GWAS meta-analysis of over 29,000 people with epilepsy identifies 26 risk loci and subtype-specific genetic architecture (Nature Genetics)

“Using aggregate human genome data for individual identification” (IEEE Xplore)

“The genetic mystery of the face” (Tia Sáng, Vietnam)

“Role of polygenic risk scores in the association between chronotype and health risk behaviors” (BMC Psychiatry)

Further Learning

This video delves into the reasons behind the longer lifespan of women compared to men, from the perspective of evolutionary psychology. It explores various factors such as genetics, culture, and evolutionary history.

“A spin-off of the popular series The Boys, Gen V immerses audiences in a near-future society grappling with the consequences of genetic enhancement. As individuals with augmented abilities, known as Gen V, navigate a world filled with moral dilemmas and societal divisions, the series delves into the ethical complexities of scientific progress.” (NewsBytes)

“AI in evolutionary psychology: a game-changer for the study of human behavior (TS2)

“Just how diverse are our mate preferences, anyway?” (Psychology Today)

“Rhetorics of species revivalism and biotechnology — A roundtable dialogue” (Animal Studies Journal)

“How the human cerebellum’s evolution makes our brains unique” (Psychology Today)

“Anti-aging mogul Bryan Johnson is ‘human guinea pig’ in $25K-per-shot experiment” (New York Post)

Disclaimer: The Genetic Choice Project makes every effort to include only reputable and relevant news, studies, and analysis on reprogenetics. We cannot fact-check the linked-to stories and studies, nor do the views expressed necessarily reflect those of the Genetic Choice Project.