Reprogenetics News Roundup #16

IVF & enhancement in the UK, Islamic ethics of germline editing, ethnic studies in PRC, WSJ on China population collapse, status & South-Korean fertility collapse, biopolitics in Eastern Europe...

Welcome to the latest issue of the Reprogenetic News Roundup! Edited by Craig Willy. Coverage of biotech policy issues has shifted to my personal blog on bio/politics, covering the intersection between biotech and international relations. Check it out to learn more about these exciting issues!

Highlights from this week’s edition:

Repro/genetics

The House on debates on IVF and genetic enhancement in the United Kingdom.

An Islamic analysis of the ethics of germline genome editing for preventing diseases.

The push to retract “unethical” studies on ethnic minority groups in China.

Population Policies & Trends

The Wall Street Journal on China’s population collapse: forecast on current trends to fall from 1.4 billion to 525 million by 2100.

“Education fever,” status externalities, and fertility collapse in South Korea.

Genetic Studies

Further Learning

Book: Biopolitics in Central and Eastern Europe in the 20th Century

Repro/genetics

“Second age of eugenics”: Would you select an embryo for its chances of higher intelligence? (The House, United Kingdom)

Leading British politics publication The House looks at parents’ growing reproductive options enabled by reprotechnologies.

The National Health Service (NHS) is about to offer whole genome sequencing to healthy newborns.

Bangladeshi-American geneticist Razib Khan hit headlines a decade ago when he sequenced his son’s genome in utero. Khan told The House he was looking for “any noticeable disease mutations, but the probability of that was super low. Mostly it was proof of principle: can I do it?”

Khan has declared that we are in the “second age of eugenics.”

Americans are employing preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) for both monogenic disorders (such as hemophilia and cystic fibrosis) and polygenic disorders (such as diabetes and heart disease).

Khan is not worried about embryo selection for desirable complex traits such as intelligence: “There’s going to be less suffering in the world. People are going to be better-looking, healthier and smarter—what’s not to like? But the main issue is you smooth out all the rough edges, and you might over-optimise.”

The world’s richest are increasingly using IVF and surrogacy. Billionaire Elon Musk used IVF for five of the six children he had with his first wife, and to have another set of twins with Shivon Zilis, a senior employee at a company he founded.

According to Walter Isaacson’s 2023 biography Elon Musk, Zilis had children with Musk because, in her words: “He really wants smart people to have kids, so he encouraged me to.”

Khan says there is some risk embryo selection will lead to a loss of genetic variation but that this is “pretty far in the future.”

Brexit mastermind Dominic Cummings predicted on his blog in 2014—while advising Michael Gove at the Department for Education—that parents in the future would inevitably select embryos for intelligence. His worry was that this would only be available to the rich and he therefore suggested that “a national health system should fund everybody to do this.”

In the United Kingdom, embryo selection is only legal to avoid the most serious inherited illnesses and regulators predict it will stay that way for the foreseeable future.

“Whether you can think so mechanically about intelligence like this is hugely simplified, very controversial, and it’s not lawful here,” says Peter Thompson, chief executive of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), which regulates fertility services and human embryo research in the UK.

“There is no federal regulation of any of this stuff in America. As a result, while clearly some very good work goes on in American labs, the concerns are that people are offered things which—even if they’re not unsafe—are unproven and are being over-claimed for.”

Thompson continues: “It may be over time that some of this polygenic risk scoring is proven to be effective. But our worry at the moment is that this is being offered in other parts of the world where the evidence base is not robust at all.”

The Newborn Genomes Programme, set to determine the genetic information of 100,000 babies, will be launched imminently by Genomics England, a company set up by the Department of Health. It ran a now-completed 100,000 Genomes Project which sequenced whole genomes from NHS patients. Instead of the heel prick test currently offered to babies on the NHS, which looks for nine conditions (soon to be 10), their whole genome will be sequenced and many more conditions will be tested for.

Professor Frances Flinter, a clinical geneticist who sits on the HFEA board, has doubts about the science and fears sequencing of newborns may lead to false positives.

Richard Scott, interim chief executive of Genomics England, said: “What we’re looking for are rare, severe, treatable conditions. We’re doing this because of the thousands of children who are born each year with these conditions where one can potentially avoid harm. The conditions that we’re looking for, almost all have a follow-on test that one can do following the genomic test … a simple way to confirm whether or not the child has the condition.”

HFEA’s Peter Thompson said : “You can see the possibility in time that more people may be requesting things like embryo screening.”

While screening embryos for traits other than serious illnesses is currently illegal in Britain, there is little regulators can do to prevent genetic tourism to the United States or other more bioliberal jurisdictions.

Ethics of germline genome editing to prevent genetic diseases from an Islamic perspective (PET)

The article analyzes germline genome editing to prevent genetic diseases based on Islamic legal maxims (Qawaid Fiqhiyyah).

Currently, the overwhelming majority of Islamic scholars agree that genome editing for human enhancement is prohibited (haram). This would be tantamount to tampering with God's creation (Taghyir Khalq Allah), as attested by several fatwas (religious rulings) issued by Islamic organisations.

The first legal maxim related to Qaṣd (intention) refers to evaluating new medical technologies based on its objectives. The key objective of therapeutic germline genome editing is to enable Muslims, who are carriers or affected with a genetic disease, to have healthy blood-related offspring of their own. Resorting to donated egg or sperm is explicitly prohibited by the Sunni branch of Islam, as this is considered akin to adultery. Germline genome editing instead of gamete donation would align with one of the five key objectives of sharia law (Maqasid al-Shariah): the protection of lineage or progeny (Hifz al-Nasl).

The authors argue germline editing is not justifiable under the legal maxims of Yaqin (certainty) and Ḍarar (preventing harm) given the uncertainties and risk of the procedure to the unborn. Instead, the safer procedure of preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) is preferable.

Under the maxim of Ḍarurah (necessity), the authors argues preventing a disorder in the unborn is less urgent than curing a born person, therefore the latter should have priority in health policies.

The authors concede there may be some cases whereby genome editing could be preferable to PGT. For example, rare instances whereby both parents are affected with the same genetic disease.

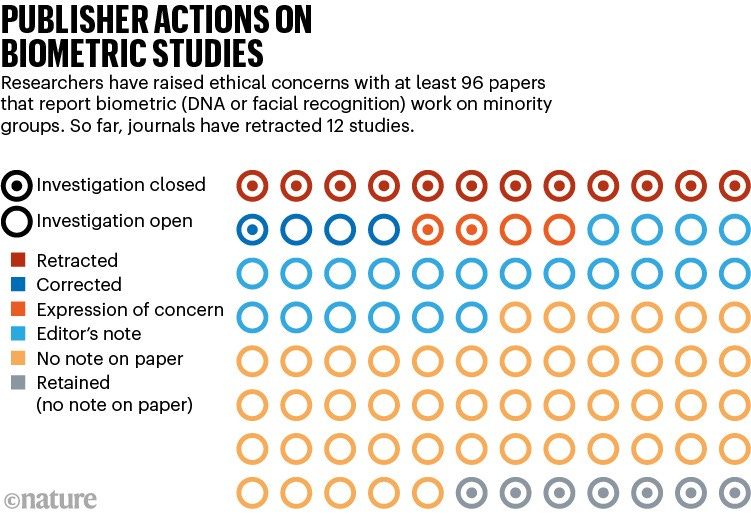

Unethical studies on Chinese minority groups are being retracted — but not fast enough, critics say (Nature)

Academics and human rights groups are raising concerns about collection of genetic data from vulnerable or oppressed minority groups.

In 2022, Human Rights Watch, had reported that a mass DNA-collection of Tibetan populations, with concerns about lack of consent and empowering surveillance by the Chinese authorities.

Twelve of 92 articles flagged by critics have been retracted by journals so far.

Yves Moreau, a computational geneticist at the Catholic University of Leuven (KUL, Belgium), urged the European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG) to take a stand against a state-run program in to collect and catalogue genetic profiles from citizens and foreign visitors. As a result of the media attention, the Kuwaiti parliament repealed the law a year later.

The success of the campaign was intoxicating: “I felt like the lucky guy who goes to the casino and bets everything on seven and wins,” says Moreau. “Of course, I had to do more.”

In 2016, Moreau learnt that DNA profiling was being deployed as part of the passport registration process in China’s northwestern province of Xinjiang, home to the mostly Muslim Uyghur minority ethnic group.

Academic papers described research to distinguish people’s ethnicity from their faces: journalists have since reported that authorities in Xinjiang have used surveillance cameras with facial recognition software to identify Uyghur faces.

In government contracts, Chinese firms developing facial-recognition software and cameras offer the ability to recognize the faces of Uyghurs or Tibetans.

When asked about concerns over the use of biometric data in China relating to minority ethnic groups, a Chinese government representative told Nature: “China is a country governed by law. The privacy of all Chinese citizens, regardless of their ethnic backgrounds, are protected by law.”

Abduwel Ayup, an Uyghur linguist who detained for 15 months by the Chinese authorities, says that no consent forms obtained in Xinjiang can be trusted, especially those gathered since around 2014, when the Chinese government began clamping down on Uyghurs and other minority ethnic groups in the region. “No one says, ‘no’,” says Ayup, because of fear of the consequences.

Most of the flagged articles have at least one co-author who works for a public-security bureau or other law-enforcement entity.

Dennis McNevin, a forensic geneticist at the University of Technology Sydney in Australia, who co-authored one of the papers, says that in many countries “it is not unusual for police to help facilitate forensic population-genetics research.” The journal Genes, for instance, decided that no action was needed for seven articles that it published. The journal’s said authors sent ethical-oversight documentation and the studies’ institutional review boards confirmed their validity.

In the wake of Moreau’s complaints, some publishers have updated their policies on informed consent and their guidance to editors on considering work from potentially vulnerable groups.

More on repro/genetics:

“Nisha IVF Centre introduces preimplantation genetic testing for enhanced success in IVF cycles” (PNN, India)

Center for Genetics and Society publishes anti-eugenic “Principles for Global Deliberations on Heritable Genome Editing” (CGS)

Upcoming online event (21 Feb): “DNA identities: Narrative and authority in genetic ancestry performance on YouTube” (American Folklore Society)

“Inside the fight for indigenous data sovereignty” (Atmos)

“Hungry gut” vs. “hungry brain”: Test could help decide who gets obesity drugs (Axios)

Population Policies & Trends

“How China miscalculated its way to a baby bust” (Wall Street Journal)

Births in China fell by more than 500,000 last year, according to recent government data, accelerating a population drop that started in 2022.

Officials cited a quickly shrinking number of women of childbearing age—3 million fewer than a year earlier—and “changes in people’s thinking about births, postponement of marriage, and childbirth.”

Researchers from Victoria University (Australia) and Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences) predict China will have just 525 million people by 2100.

China’s fertility rate is approaching 1 birth per woman, down from around 3 in the 1970s.

Song Jian, a a Chinese rocket scientist and mathematician, presented demographic projections to Chinese officials after 1979. He reportedly used “a frightening narrative of a coming demographic-economic-ecological crisis” to persuade people of the risks of overpopulation. The one-child policy was set up nationwide in 1980.

Women raised under the one-child policy grew up being told of the need to have a smaller but “higher-quality” population.

Beijing says the one-child policy prevented 400 million births, a claim it is has often put forth as a kind of gift to the world, including at the 2009 climate summit in Copenhagen.

In 2015, China switched to a two-child policy and since then to a “birth-friendly culture” encouraging more than two.

Yi Fuxian, a senior scientist in obstetrics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has long argued that the situation is worse than official Chinese data suggests. He believes China’s population began shrinking years ago, based on birth estimates pieces together form other available data.

Yi said: “All of China’s population policies for decades have been based on erroneous projections. China’s demographic crisis is beyond the imagination of Chinese officials and the international community.”

“Fertility is a collective action problem. Can it be tackled with taxation?” (The Great Gender Divergence/Alice Evans)

Alice Evans argues that South Korea’s world-leading ultra-low fertility rate (0.78 in 2022) is related to the society’s “education fever” with most children attending after-school private tuition (hagwons).

She cites a paper in the American Economic Review showing that parents care about their child’s relative education compared to their peers. The authors call this a “status externality”: competition drives up investment, increasing costs, ajd lowering fertility. The authors believe taxation can help address the issue.

The poorest families typically have 1.80 children, while the richest have 2.03. Poorer families are also more likely to be entirely childless.

75% of children are enrolled in after-school programs and with private tutors.

Curfews recently banned private education after a certain time of day (22:00 or 23:00). These lowered spending on private education among rich families, which then reduced education spending by low-income families.

The authors argue that taxing spending on education will lower investment and enable the poorest to catch up with the rich and have two children.

There is a global trend in rising inequality leading to increased competition and “intensive parenting.”

In China, private education has been entirely banned, but there has been a rise in underground private tuition and online learning. Illicit tutoring classes are disguised as “housekeeping.”

Evans concludes: “The educational arms race is real. The unresolved question is how to address it.”

More on population policies and trends:

Why has fertility plummeted? Insights from Hong Kong (The Great Gender Divergence/Alice Evans)

Genetic Studies

“The interplay between suicidality, substance dependence, and genetics: A comprehensive review” (Medriva)

“Psychiatric polygenic risk scores across youth with bipolar disorder, youth at risk for bipolar disorder, and controls” (Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry)

“Alzheimer’s disease candidate genes uncovered with focused analysis method” (genomeweb)

“A genetic cause for low eight children born through assisted reproduction (Le Spécialiste)

“Immunotherapy for colorectal cancer: insight from inherited genetics” (Trends in Cancer)

“Is the genetic architecture of behavior exceptionally complex?” (Current Opinion in Insect Science)

Further Learning

Biopolitics in Central and Eastern Europe in the 20th Century: Fearing for the Nations (Routledge)

This book is the first to provide a comprehensive view on biopolitics for Central and Eastern Europe in the twentieth century, defined as issues of health and hygiene, birth rates, fertility and sexuality, life expectancy, and demography to eugenics and racial regimes.

The volume collects the latest research and empirical studies from the region to showcase the diversity of biopolitical regimes—from hunger relief for Hungarian children after the First World War to abortion legislation in communist Poland.

Biopolitical strategies in the region often revolved around the notion of an endangered nation.

More on biotech and evolution:

“Experimental gene therapy allows kids with inherited deafness to hear” (TIME)

“Gene mutation helps Andean highlanders thrive at altitude, and ‘living fossil’ fish live deep underwater” (Live Science)

“Revolutionary animal-free system for cultivating human embryonic stem cells” (BNN)

“Cops used DNA to predict a suspect’s face—and tried to run facial recognition on it” (Wired)

Conservative Alaska publication compares use of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) in health policy to “eugenics” and “senilicide by Alaska Natives (putting a burdensome elder on an ice floe) (Must Read Alaska)

Disclaimer: We cannot fact-check the linked-to stories and studies, nor do the views expressed necessarily reflect our views.