Reprogenetics News Roundup #19: Will the right to IVF be protected?

1st US IVF baby talks IVF, Anomaly and Billauer on embryo selection, Japanese fertility by wealth/education, Pakaluk on large families, learning from ancient genomes

Welcome to the latest issue of the Reprogenetic News Roundup! Edited by Craig Willy. Highlights from this week’s edition:

Repro/genetics

Elisabeth Carr, America’s first IVF baby, on the threats to IVF

Jonathan Anomaly on a bioconservative case for embryo selection

Barbara Pfeffer Billauer on the state of play of embryo selection for health and enhancement

Population Policies & Trends

Educated and wealthier Japanese have tended to have more children than others

Catherine Pakaluk on women with large families

Genetic Studies

Ancient genomes and possible selection for intelligence and other traits.

Further Learning

Repro/genetics

“I was America’s first IVF baby: After attending the State of the Union, here’s what I want you to know” (Boston Globe)

Elisbath Carr, America’s first IVF baby, attended President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address. She writes on recent controversy around IVF in the U.S.

The Alabama Supreme Court’s declaring frozen embryos children is “a devastating blow to the hopes of those longing to start or expand their families through assisted reproductive technology.”

Alabama Governor Kay Ivey has signed a bill into law approving legal protections to providers of IVF services, but that doesn’t undo the court’s ruling that embryos should be treated like people.

On December 28, 1981, Elisabeth Carr became the first baby born in the United States via IVF. The treatment was controversial, and as-yet unproven in the United States, although there had been successes abroad with the world’s first IVF baby, England’s Louise Brown.

After birth, doctors announced that Carr was a “normal” and “healthy” baby girl.

Test-Tube Babies: A Daughter for Judy is a documentary about her life.

In that time, a lot has changed. “Octomom” gave birth to eight children through IVF in 2009. Her case sparked debate within the field that perhaps single embryo transfer should once again become the standard of care in most cases, and now it is. Egg freezing is common, but was initially controversial.

Back in 1990, when the first preimplantation genetic testing for a monogenic disease was done (monogenic diseases include cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy), there was huge controversy. Nowadays it is common to undergo testing to screen for them. Other forms of preimplantation of genetic testing remain controversial.

There are 12 million people born from IVF worldwide.

President Biden called on Congress to “guarantee the right to IVF” nationwide.

Richard Hanania writes that attacks on IVF may trigger stronger protections.

“IVF, embryo selection, and the case for caution: What we can learn from Chesterton’s Fence (Psychology Today)

Philosopher Jonathan Anomaly writes on selecting embryos for reduced risk of diseases and traits like intelligence in the context of IVF.

As IVF becomes cheaper and polygenic prediction more accurate, many parents will do IVF electively to consciously select among genetically diverse embryos.

Polygenic screening has obvious benefits, like boosting the chance that children will have healthy and happy lives.

We must distinguish when skepticism about new technologies like polygenic screening reflects psychological prejudice, such as status quo bias, and when it might be justified.

“Chesterton’s Fence” is a call for caution: We should understand the point of a fence—an existing barrier— before we tear it down.

However, unlike gene editing, embryo selection doesn’t introduce new risks to the IVF process. Instead, it gives us a sense of which embryo is less likely to develop a disease that we worry about—or more likely to possess a trait that we care about.

When editing is safer, using gene editing to “spell check” an embryo may be as common as using software editing tools to spellcheck an essay you’ve composed on your computer.

Eventually, a combination of embryo selection and gene editing may be essential just to stay where we are now, because the modern world has been quietly fostering the accumulation of deleterious mutations in all of us. The safety and medicine of modern societies strongly reduces natural selection’s weeding out of harmful mutations.

Charles Darwin worried about the collective consequences of these interventions, but still supported them for humanitarian reasons: “With savages, the weak in body or mind are soon eliminated; and those that survive commonly exhibit a vigorous state of health. We civilized men, on the other hand, do our utmost to check the process of elimination; we build asylums for the imbecile, the maimed, and the sick; we institute poor laws; and our medical men exert their utmost skill to save the life of everyone to the last moment… No one who has attended to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that this must be highly injurious to the race of man.” (The Descent of Man, 1871).

Darwin hoped that a better understanding of genetics might lead us to solutions like “judicious marriages” and other non-coercive interventions to prevent genetic deterioration.

A century and a half later, it’s possible we can mimic the benefits of natural selection by using genetic technology to minimize the likelihood that our children will suffer from the consequences of novel mutations.

“Chesterton’s Post” is a call for action: Sometimes we need to intervene just to preserve what already have.

The late evolutionary psychologist John Tooby argued that if we don’t embrace genetic engineering we will eventually suffer “genetic meltdown”: when we spend a steadily increasing amount of our time and resources trying to fight the consequences of harmful mutations with medications and social interventions.

Anomaly concludes those who reject radical human enhancement may need to embrace some genetic engineering to keep what we have now: “We may need to keep repairing the post just to preserve the parts of it that we cherish.”

“Genetic embryo screening for health issues and IQ inch closer to reality: Here’s a primer on what you can expect” (Genetic Literacy Project)

The IVF labs offering genetic selection tests are based in New Jersey and California. We can expect a host of genetic tourism to ensue.

“Once upon a time, if you wanted a tall, handsome, healthy child, you married a tall, good-looking, healthy spouse. That approach isn’t always reliable, since by virtue of genetic laws two tall people still have a respectable chance of having a short, gawky kid, and numerous extrinsic factors, including the environment, impact both height and health.”

Pre-natal genetic screening to select particular embryos for birthing based on the genetic traits desired is commercially available in the U.S. Use of these technologies is circumscribed only by the few voluntary guidelines produced by medical organizations.

Post-natal genetic screening was first used and legally mandated, in 1963 to identify babies born with PKU, a devastating metabolic disorder that can be prevented by diet.

Adult use of wide-spectrum genetic screening, utilizing Genome-Wide Associations Studies (GWAS), is now commonly available to identify disease risks that can be relieved or possibly prevented by lifestyle or environmental changes.

For example, assessing for the presence of BRCA 1 and BRACA mutations may lead to earlier detection and more effective breast cancer treatment.

Gene therapy utilizing bespoke drugs or use of modified genes can remedy certain conditions, even in utero. Valid uses for post-conception genetic screening abound.

In conjunction with IVF, prenatal genetic testing (PGT) is conventionally employed to deselect embryos with Mendelian abnormalities. i.e., those with certain and serious adverse post-birth outcomes, or those which would have difficulty implanting.

Another use of PGT is identifying embryos to generate compatible tissue for transplantation to an already born, but ill, child, called savior siblings. The technique was first effectuated almost a quarter of a century ago, and the practice is controversial, accounting for only 1% of PGT done today.

At least two American laboratories reportedly claim to identify the healthiest embryo of the IVF litter for selection. The technique predicts risks of disease. The service provides a cumulative health ranking, called the polygenic risk score (PGS), grading the genetic predisposition for numerous conditions.

The prospective parent, in basing their embryo selection on genetic risk indicators, theoretically has the option of configuring a kid with the most brains or brawn or beauty. Although these techniques are not currently on the table, , the possibility has incited ethical outrage.

“Accurate IQ predictors will be possible, if not the next five years, the next 10 years certainly.”—Stephen Hsu of Genomic Prediction, a commercial marketer of PGT technology

“You are not going to stop the modeling in genetics, and you are not going to stop people from accessing it. It’s going to get better and better.”— Matthew Rabinowitz, CEO of the prenatal-testing company Natera

Bioethicists currently questions PGT for probablistic traits based on analytic validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility. But these concerns will become less relevant once the techniques become more precise and a greater body of data is generated.

Bioethicists also judge interventions “in Brutus-like obeisance, without specific anchor” to the traditional bioethical precepts: autonomy, beneficence and non-maleficence (fancy ways of saying harms and benefits), and social justice.

A specific structural basis to decide what is ethical in this context is missing, a fact lamented and recognized by Ronald J. Wapner, director of Reproductive Genetics at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

“Use of AI embryo selection based on static images to predict first trimester pregnancy loss” (Reproductive BioMedicine Online)

The study investigated the use of an artificial intelligence (AI) embryo selection assistant to predict the incidence of first trimester spontaneous abortion using static images of IVF embryos.

ERICA™ AI grouped embryos into different categories. Optimal/Good embryos had a lower incidence of spontaneous abortion (16.1%) compared to embryos classified as Fair/Poor (25%).

The authors conclude that ERICA™ AI, which was designed as a ranking system to assist with embryo transfer decisions and ploidy prediction, might also be useful in providing information for couples on the risk of spontaneous abortion. Future work will include larger sample size and karyotyping of miscarried pregnancy tissue.

More on repro/genetics:

“Why does polygenic selection help?” (Astral Codex Ten)

“The ethics of preimplantation genetic diagnosis: A case study of babies born free of osteogenesis imperfecta” (Breaking Latest News)

On right-to-try laws: “My daughter has a rare disease: We shouldn’t have had to leave the US to save her life” (USA Today)

Population Policies & Trends

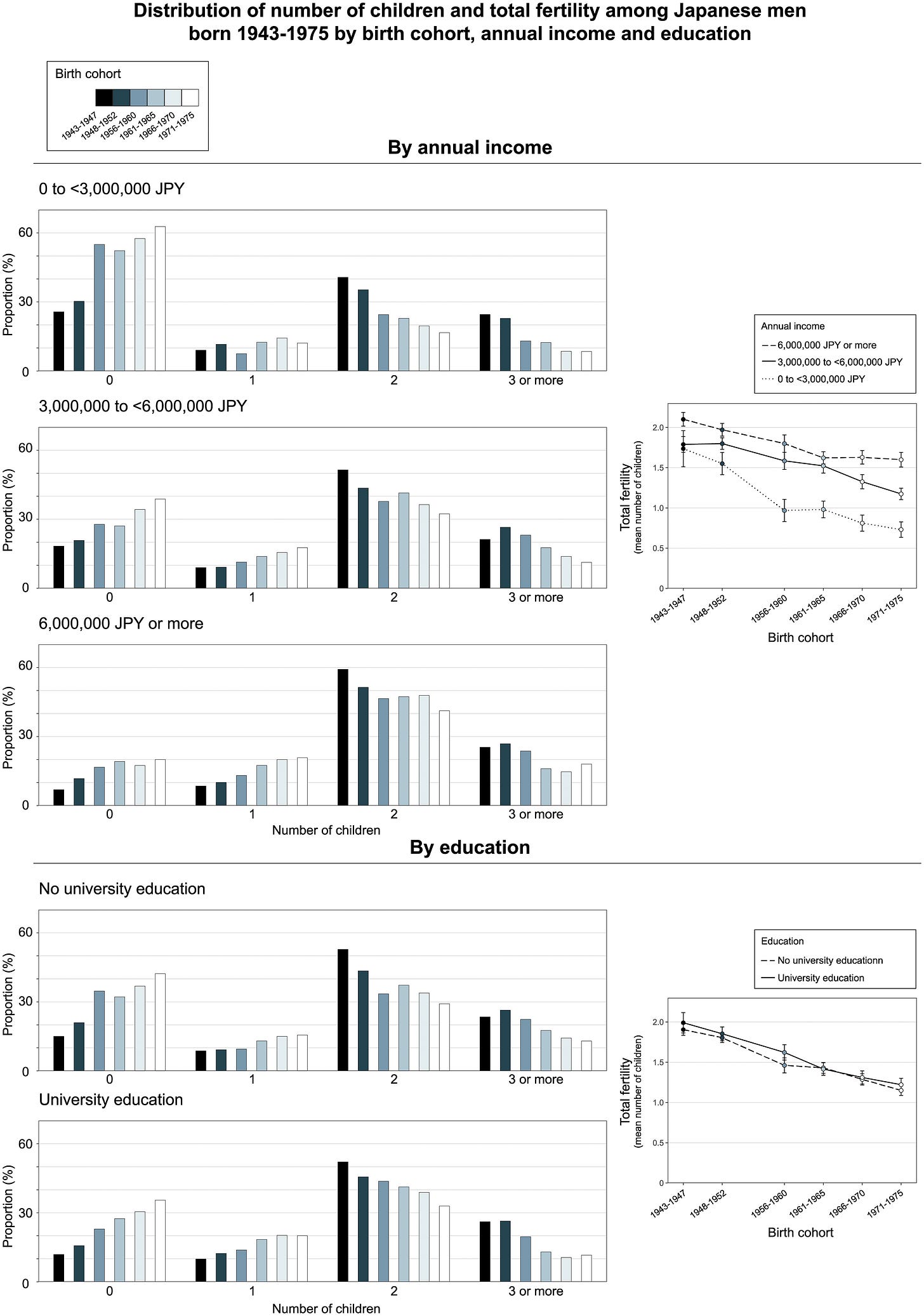

“Salaries, degrees, and babies: Trends in fertility by income and education among Japanese men and women born 1943–1975” (PLOS ONE)

For men, those with a university degree were more likely to have children than those without a university degree in all birth cohorts except 1943–1947.

Men with higher income were more likely to have children across birth cohorts.

While the proportion who had children decreased in all income groups, the decrease was steeper among those in the lowest income group.

Among women born 1956–1970, those with a university degree were less likely to have children than those without a university degree. This difference was no longer seen among those born 1971–1975.

Busch School of Business Associate Professor Catherine Pakaluk discusses her forthcoming book, Hannah’s Children, about women having large families in a culture of childlessness, the limits of economic and family policy in reversing the falling birthrates, and what is driving demographic decline.

More on population policies and trends:

“The data is clear: People are having less sex” (Graphs About Religion)

Genetic Studies

“What do ancient genomes show about recent human evolution? Results from 2625 ancient European genomes” (Emil Kierkegaard)

David Piffer and Emil Kierkegaard used data from 2625 ancient European genomes to retrace which traits have been under evolutionary pressure over the past 12,000 years.

The authors found positive selection for genes associated with educational attainment, intelligence, autism, and height, and selection against schizophrenia, depression, and neuroticism.

Kierkegaard suggests intelligence maybe a major trait that has been selected for, given that it has all traits with positive genetic correlations with intelligence are under positive selection, and those with negative genetic correlations are under negative selection.

There are some non-continuous changes in some genetic scores related to population replacement, namely of hunter-gatherers by Anatolian farmers. The farmers seem to be smarter than the hunter-gatherers and replacement increased intelligence faster than within-group selection would have done. Kierkegaard calls this: “Group selection in action.”

More on genetic studies:

“The genetic of loneliness and its impact on health” (23andMe blog)

Further Learning

“How did altruism evolve?” (Quanta Magazine)

“Physical attractiveness of potential competitors influences women’s gossip: Effects of romantic jealousy and self-esteem” (Evolutionary Psychological Science)

Shortening organ donor waiting lists: eGenesis, PorMedTec engineer pig donors in Japan for xenotransplantation (Gen Eng News)

“An evolutionary explanation of the Madonna-Whore Complex” (Evolutionary Psychological Science)

Disclaimer: The Genetic Choice Project cannot fact-check the linked-to stories and studies, nor do the views expressed necessarily reflect our own.