Repronews #41: Progress towards artificial wombs

JD Vance's natalism; births by region since 1950; self-control 60% heritable; Homo sapiens vs. Neanderthals; continued human evolution

Welcome to the latest issue of Repronews! After the summer summer break, we resume our regular posting. Highlights from this week’s edition:

Repro/genetics

Prospects for artificial wombs

Population Policies & Trends

Republican vice-presidential candidate J. D. Vance has long promoted natalism

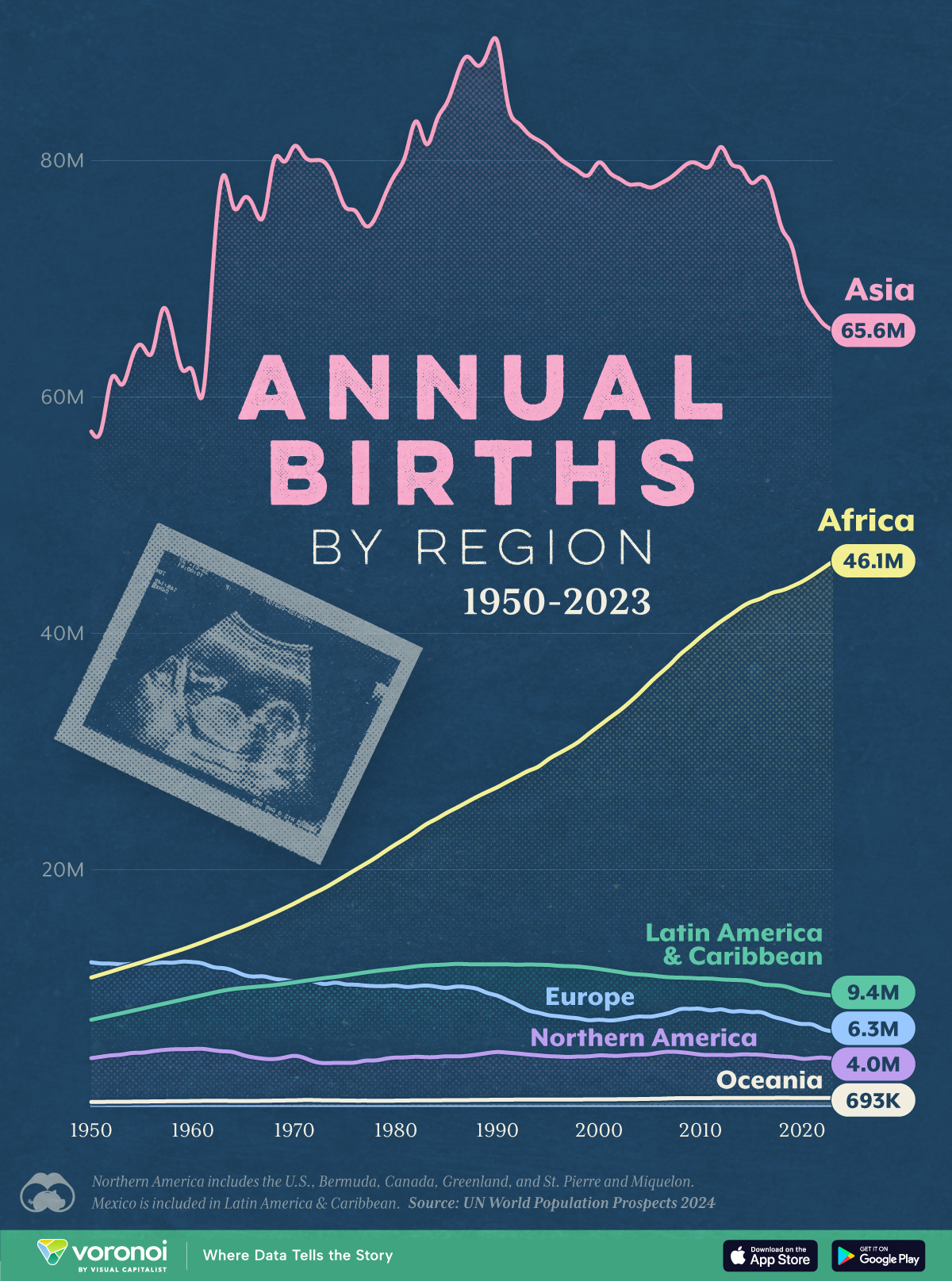

Visualized: the number of people born every year by region since 1950

Genetic Studies

Self-control is about 60% heritable

Further Learning

Why did Homo sapiens outcompete Neanderthals?

Are humans still evolving?

Repro/genetics

“Artificial wombs when?” (Asterisk Mag)

Last September, advisors to the FDA met to discuss artificial wombs which might be available in just a few years.

Artificial wombs present the prospect of allowing mothers to skip pregnancy altogether and gestate the fetus in a machine outside the body.

For now research into artificial wombs is focused on continuing gestation of extremely premature infants born “at the cusp” of viability. Children born at this stage—between 22 and 28 weeks—have high mortality rates and carry high risks of disability if they survive. 6% of all US preterm births fall into this extremely premature category.

Incremental progress in adjusting the designs of these “artificial placenta” systems has pushed the date of viability earlier and earlier. A successful prototype, created by a team at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in 2017, kept premature lamb fetuses alive for four weeks in a “biobag” circulating synthetic amniotic fluid.

Other groups have kept premature lambs alive with the help of artificial placenta devices. These include scientists at the University of Western Australia and the University of Michigan, both in 2019.

The Philadelphia researchers are currently in discussions with the FDA about moving toward testing the “biobag” on extremely premature human infants.

These types of “artificial placenta” or “ectogenesis” devices do not attempt to replicate all the functions of the uterus. Current artificial wombs are primarily mechanical—not chemical—devices. They pump the fetus’s deoxygenated blood into an oxygenator and then freshly oxygenated blood back into the fetus, just as the placenta normally does in utero and the lungs and heart do in healthy infants.

In contrast, a biological uterus has complex signaling mechanisms involving hormones, immune system modulation, gene expression, and epigenetic modifications, all of which contribute to fetal development. Many of these processes are poorly understood, and more are certainly unknown.

When people talk about “artificial wombs” being imminent, they usuallly mean ectogenesis for prematurity—essentially an advanced form of life support. This will not necessarily lead to full end-to-end artificial wombs. The biobag doesn’t address the hardest part: early development in the first weeks of pregnancy.

Artificial gestation of mice has been explored in studies, though not to birth.

The author argues that artificial wombs to replace pregnancy are not going to be developed any time soon and face challenging obstacles.

The article also explores emerging technologies of genetic screening, in vitro gametogenesis (e.g., creation of ovaries in the lab), and delaying menopause.

More on repro/genetics:

New Australian Capital Territory fertility law eliminates donor anonymity (PET)

“Event review: Polygenic embryo screening—the promise and perils of selecting our children’s traits” (PET)

Population Policies & Trends

“Why JD Vance worries about childlessness” (Wall Street Journal)

Donald Trump’s vice-presidential running mate J. D. Vance has linked Americans’ reluctance to have children to high high housing costs, risk aversion and a culture of social isolation.

The Ohio Republican has come under scrutiny for criticizing people who don’t have children. In 2021, he told Fox News that the U.S. was being run by “a bunch of childless cat ladies who are miserable at their own lives and the choices that they’ve made, and so they want to make the rest of the country miserable, too.”

After joining the Senate last year, Vance became one of the most outspoken lawmakers about the decline in U.S. fertility. The total fertility rate—a snapshot of how many children a woman is expected to bear over her lifetime—fell to 1.62 last year, provisional government figures show, the lowest on record, and well below the 2.1 replacement rate needed to keep population steady.

In an interview in April with the Wall Street Journal, Vance described low fertility as having many causes, no simple remedy, and negative consequences beyond simply a smaller workforce and less sustainable programs such as Social Security.

“A very important part of kids’ social development obviously is spending time with other kids,” Vance said. But with lower birthrates, “you have a lot less brothers and sisters, you also have many, many fewer cousins. I think childhood has become much more socially isolated.”

“I do think there’s just something about the economies of having families that have really gotten out of whack,” Vance added. He cited high housing costs in particular.

Vance also linked lower birthrates to young Americans growing up more socially isolated. “They’re not spending as much time socially together,” he said. “They’re certainly not dating as much as they used to.” This manifests itself as “less marriage, much thinner friendship groups.”

Vance argued lower fertility might also be the result of less patriotism. In Israel, which has relatively high fertility, “there’s still a fundamental sense that they love their country, they want their country to keep going. America was always considered by our European friends to be kind of jingoistic back in the 1990s and 2000s. We had pretty healthy fertility rates back then. Now that we’re a little bit more like our European counterparts, much less sort of innately patriotic than we were 20, 30 years ago, our fertility rates have declined.”

While Vance has studied pronatalist policies in countries including South Korea, France, Hungary and Japan, he said he hasn’t yet seen any clear solution to falling fertility. “I’m fascinated by Hungary … because they’re aggressively trying a lot of different things. And I think some of it’s working.” The U.S. should look at lowering income-tax rates on women who have multiple children as Hungary has done, he said.

In a 2021 interview, before he was a senator, Vance had said that people without children should pay higher tax rates than people who have children. (Some provisions of the current tax code, such as the child tax credit, have that effect.)

Vance has previously floated the possibility of giving parents extra votes for their children.

The number of people born every year, by region (Visual Capitalist)

Asia’s annual births peaked at 90 million in 1990, but there’s been a steep drop since 2012 to 65 million.

Meanwhile, the number of people being born each year in Africa has been rising quickly. In 2023, Africa recorded 43 million births. Current UN projections estimate an increase every year until it peaks at 56 million in 2067.

Births in other regions have been relatively steady, with slight downtrends seen in Europe, and more recently, Latin America.

Countries in Europe and northeast Asia in particular are aging because of the decline in births, casting doubts over the sustainability of social welfare systems. An aging population can also disrupt the economy, both through the workforce and a shift in demand. Healthcare costs, for example, will increase, raising the requirement for doctors, nurses, and related health workers.

All figures were sourced from the UN World Population Prospects 2024.

More on population policies and trends:

“Australia in biggest ‘baby recession’ since 1970s as pandemic birth boom fades” (Guardian)

Japan’s population shrank for the fifteenth year in a row, by 861,000 (0.7%), despite the arrival of 329,500 foreign residents (an 11% increase) (Japan Times)

“The movement desperately trying to get people to have more babies” (Vox)

“The real reason people aren’t having kids” (The Atlantic)

Genetic Studies

“The nature and nurture of self-control: Self-control is around 60% heritable” (Steve Stewart-Williams)

Identical twins are more similar in self-control than the non-identical twins, indicating that genes play a considerable role in shaping this important trait.

Self-control is around 60% heritable, meaning genes explain roughly 60% of the differences between individuals in their levels of self-control.

A meta-analysis of heritability studies on self-control found that shared family environment had no effect on self-control. In other words, twins who grew up in the same home were no more similar in self-control than those who grew up apart.

Heritability of self-control was the same for men and women.

More on genetic studies:

“New study addresses long-standing diversity bias in human genetics” (Johns Hopkins University)

Further Learning

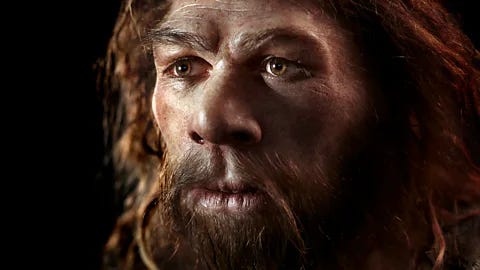

“Neanderthals vs Homo sapiens: How social structures affected ancient species’ ability to survive” (Nicholas Longrich/GLP)

Why did Homo sapiens outcompete and replace Neanderthals? It probably was not because of individual smarts, as Neanderthals were intelligent and had larger brains.

It may be that the key differences were less at the individual level than at the societal level. It’s impossible to understand humans in isolation, any more than you can understand a honeybee without considering its colony. We prize our individuality, but our survival is tied to larger social groups, like a bee’s fate depends on the colony’s survival.

Modern hunter-gatherers provide our best guess at how early humans and Neanderthals lived. People like the Namibia’s Khoisan and Tanzania’s Hadzabe gather families into wandering bands of 10 to 60 people. The bands combine into a loosely organised tribe of a thousand people or more.

These tribes lack hierachical structures, but they’re linked by shared language and religion, marriages, kinships and friendships.

Neanderthal societies may have been similar but with one crucial difference: smaller social groups. This is suggested by Neanderthals’ lower genetic diversity.

In small populations, genes are easily lost. If one person in ten carries a gene for curly hair, then in a ten-person band, one death could remove the gene from the population. In a band of fifty, five people would carry the gene – multiple backup copies. So over time, small groups tend to lose genetic variation.

In 2022, DNA was recovered from bones and teeth of 11 Neanderthals found in a cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia. Several individuals were related, including a father and a daughter–they were from a single band. And they showed low genetic diversity. Low diversity suggests they lived in small bands—probably averaging just 20 people.

It’s possible Neanderthal anatomy favoured small groups. Being robust and muscular, Neanderthals were heavier than us. So each Neanderthal needed more food, meaning the land could support fewer Neanderthals than Homo sapiens.

And Neanderthals may have mainly eaten meat. Meat-eaters would get fewer calories from the land than people who ate meat and plants, again leading to smaller populations.

If humans lived in bigger groups than Neanderthals it could have given us advantages, notably in warfare. Big societies have other, subtler advantages. Larger bands have more brains. More brains to solve problems, remember lore about animals and plants, and techniques for crafting tools and sewing clothing. Just as big groups have higher genetic diversity, they’ll have a higher diversity of ideas.

More people also means more connections. Network connections increase exponentially with network size, following Metcalfe’s Law. A 20-person band has 190 possible connections between members, while 60 people have 1770 possible connections.

Information flows through these connections: news about people and movements of animals; toolmaking techniques; and words, songs and myths. Plus the group’s behaviour becomes increasingly complex (culminating in things like buildings, cars, modern warfare, and computers).

Group intelligence even works with ants. Individually, ants aren’t smart. But interactions between millions of ants lets colonies make elaborate nests, forage for food and kill animals many times an ant’s size.

Humans aren’t unique in having big brains (whales and elephants have these) or in having huge social groups (zebras and wildebeest form huge herds). But we’re unique in combining them.

Throughout history, humans formed larger and larger social groups: bands, tribes, cities, nation states, international alliances.

It may be then that an ability to build large social structures gave Homo sapiens the edge, against nature, and other hominin species.

“Yes, humans are still evolving” (Popular Science)

Noted public figures like David Attenborough have previously claimed that human evolution is over, but many researchers studying human evolution firmly disagree.

Humans have altered our environment in innumerable ways–changing the very air, water, and soil that we rely on as the most successful “ecosystem engineers” on Earth. It can be easy to then assume that we’ve conquered biology and eliminated the effects of evolution and natural selection on our species. But that’s not what the science says.

“Of course humans are still evolving,” says Jason Hodgson, an anthropologist and evolutionary geneticist at Anglia Ruskin University in England. “All living organisms that are in a population are evolving all the time.”

“Humans are still evolving, as are virtually all other populations of organisms,” says Stephen Stearns, an emeritus professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Yale University.

In biological terms, evolution is a change in gene variant (a.k.a. “allele”) frequency in a population over time. It is not a force directing a species’ trajectory towards a certain goal.

Evolution can occur through different mechanisms:

De novo mutuations: Every person is born with about 70 new genetic mutations on average, which aren’t derived from their parents’. Once emerged, mutations can be passed onto subsequent generations, thereby changing population-level allele frequency.

Genetic drift: When randomness influences what gene variants are passed on in what proportions. this unfolds the quickest in small populations.

Gene flow: When individuals and populations migrate, bringing their genetic material to new places.

Sexual selection: When people mate non-randomly (which accounts for most of human mating). In nature, much of sexual selection is driven by female choice. Over time, female peahens’ esthetic preference has led to the spectacular tail and coloring of the peacock.

Natural selection: where environmental conditions that impact survival and reproduction dictate what alleles are most likely to persist through future generations. Unlike drift, natural selection happens faster in larger populations, as beneficial alleles are more likely to emerge when there are more people around. “This is the largest the human population size has ever been, so this is probably to some extent the greatest change for natural selection to act in humans,” Hodgson says.

Through all of these above mechanisms, humans evolved from our last common ancestor with our two closest living relatives–chimpanzees and bonobos. And all these mechanisms are still at play in humans today, though our societal organization and sheer numbers may have altered which ones are acting the quickest, in what populations, and in what ways.

Some drivers of human evolution that are likely unique to our species, at least in their intensity. In many instances, our cultures influence with whom, how, and whether people reproduce. Those things also go on to affect the frequency of gene variants across time. This is an example of gene-culture coevolution.

“We are maybe somewhat tweaking the course of evolution, but it doesn’t at all mean we’re stopping it from happening,” says Hakhamanesh Mostafavi, an associate professor of genetics and genomics at New York University

Many studies of humans’ genetic past provide illustrative examples of evolution in action:

The rise of malarial resistance in Madagascar, linked to the proliferation of a specific gene variant in the population, as described in 2014 research from Hodgson. That example of evolution within the past 2,000 years.

The emergence and spread of alleles that enable adult lactose digestion in some Middle Eastern, European, and African populations, following the spread of herding. “Even within the past 1,000 years, lactase persistence as an allele is increasing,” Hawks says.

Stearns and his research colleagues attributed height decreases and other population-level changes to natural selection over just one century in a classic 2010 study of people in Framingham, Massachusetts.

Studies of large genomic datasets reveal changes that wouldn’t otherwise be observable on a trait-level. A 2022 paper identified two small changes in the human genome, responsible for creating functional proteins, which emerged since our species split from other primate lineages.

“Humans are definitely still evolving,” says John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The ultimate direction of that change is unclear however.

“Today’s environments are changing really fast in various ways. We don’t know for sure which changes will be sustained over time, so we don’t know what changes might add up to anything. [Many] changes might reverse and go the opposite direction just as quickly as they evolved in the last generation or two,” Hawk adds.

“I personally think that our genetics are going to continue to change, probably at an accelerated rate,” he says, “but I do not have a good basis for predicting how.”

More on human nature, evolution, and biotech:

Human genetics

“50 times human genetics led to some unique body characteristics” (MSN)

Agriculture

“France’s Gourmey submits first EU application for cultivated meat” (Politico)

“Singapore becomes first country to sell lab-grown meat directly to the public” (GLP/NYT)

“‘Gene editing poses no unique risks’: European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) finding lowers the regulatory barrier for crop biotechnology innovation” (GLP/Transkript)

Sport

“Athletes worldwide turn to genetic screening for improved performance (Down to Earth)

Disclaimer: The Genetic Choice Project cannot fact-check the linked-to stories and studies, nor do the views expressed necessarily reflect our own.

Would it be possible yo provide news for other breakthrough technologies like gene therapy.

Life extension might be too broad so I won’t ask for this, however the multitude of applications of gene therapy is extensive and therefore worth keeping tabs on

"heritability 60% heritable" <-- self-control